History of RHD control

WHO Global Programme for the Prevention and Control of RF / RHD

Dr Nordet, Former Medical Officer, Cardiovascular Disease Programme, World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been engaged in RF/RHD control and prevention efforts since the 1950’s. The most substantial of these activities was the WHO Global Programme for the prevention of rheumatic fever / rheumatic heart disease was implemented from 1986-2002 in 16 pilot countries in high endemic regions throughout the world. Dr Porfirio Nordet, former advisor to WHO on RHD, shared his experiences as a facilitator of the Global Programme:

Components of the Program

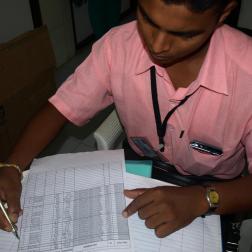

WHO provided protocols and educational materials to participating countries in addition to motivational support and modest financial backing. In exchange, countries were held responsible for regularly reporting data to WHO. The program was rolled out in phases: Phase 1 involved a single pilot site within each country. During Phase 2, project expansion into the surrounding communities took place. In Phase 3, at 5-10 years post-implementation, programs scaled-up to the national level. Progress reports were submitted to WHO on a semi-annual basis. The Global Programme focused on secondary prophylaxis but also attempted to implement robust primary prevention in 7 target countries. Secondary prophylaxis required the creation of a central registry and active case finding which was completed by direct survey of students and families for symptoms as well as a review of hospital records. An unstable supply of BPG, inadequate staff and weak reporting were all associated with lower rates of adherence to secondary prophylaxis.

Public, patient and provider education was a significant component of the program. Print media—including booklets, pamphlets and posters—were preferred forms of messaging because of their easy reproducibility and distribution. At a quick glance, they can refresh providers’ medical knowledge and improve their clinical practice, and patients can be reminded of follow-up recommendations or of the natural history of their disease, for example. Awareness campaigns also included the mass media through radio and television. Healthy lifestyle education and hygiene promotion were taught to young people in schools. A direct correlation was seen between the amount of education provided and the number of patients registered and compliant with secondary prophylaxis.

Challenges and Solutions

Follow-up was difficult for patients living far away. Recommendations were made to decentralise follow-up care to local health clinics. In addition, swabbing and culture were discouraged because of delays in returning test results and because patients often did not revisit the clinic to receive a definitive diagnosis. RF and RHD are not very common conditions for primary care physicians to manage, knowledge of diagnostic criteria and disease management naturally wanes with time. Concise and easily-readable resources, like posters and pamphlets, were considered essential for both providers and patients to most efficiently manage GAS pharyngitis and RF/RHD.

A major problem was program sustainability post-2002, after the Global Programme’s funding had been disbursed. Country reporting to the WHO slowed, probably in association with cessation of a (small) financial incentive. Structural changes at the WHO and a declining sense of international camaraderie contributed to reduced engagement after 2002. Changes in leadership and approach at the national level further reduced capacity. Sustainability was closely tied to a lasting commitment of the Ministry of Health which, in turn, requires constant advocacy by local champions. From a program’s inception, champions should be sought out through Ministries of Health by identifying well-respected experts at local institutions. Champions then assemble a network of physicians and coordinate their activities with the Ministry of Health.

Dr Nordet reflects that constant evaluation, requiring a central registry, and periodic reports and presentations to the Ministry of Health or international organizations should be part of any program to promote accountability.

Ideally, protocols supplied to countries would be locally-relevant, taking into consideration the realities on the ground. To do this, WHO staff would necessarily visit countries to assess their infrastructural strengths and limitations before drafting guidelines.